Professor Dennis Wong: Hong Kong’s Reintegration Models for Young Offenders

//16.3 Interview 2: Professor Dennis Wong

Hong Kong’s Reintegration Models

for Young Offenders

Dennis Wong, Professor of Criminology and Social Work at City University of Hong Kong, shares different models that the city employs within the judicial system to rehabilitate and reintegrate young offenders back into the community.

Professor Wong, in a paper presented at a conference long before in 2005 in Perth, Australia, reflected on the importance of mediation tactics and delinquency. He argued that giving young offenders a second chance, offering them opportunities to change their behaviour, rather than simply punishing them, labelling them negatively, stigmatising and excluding them, was a far more positive process of community development, especially in the long term.

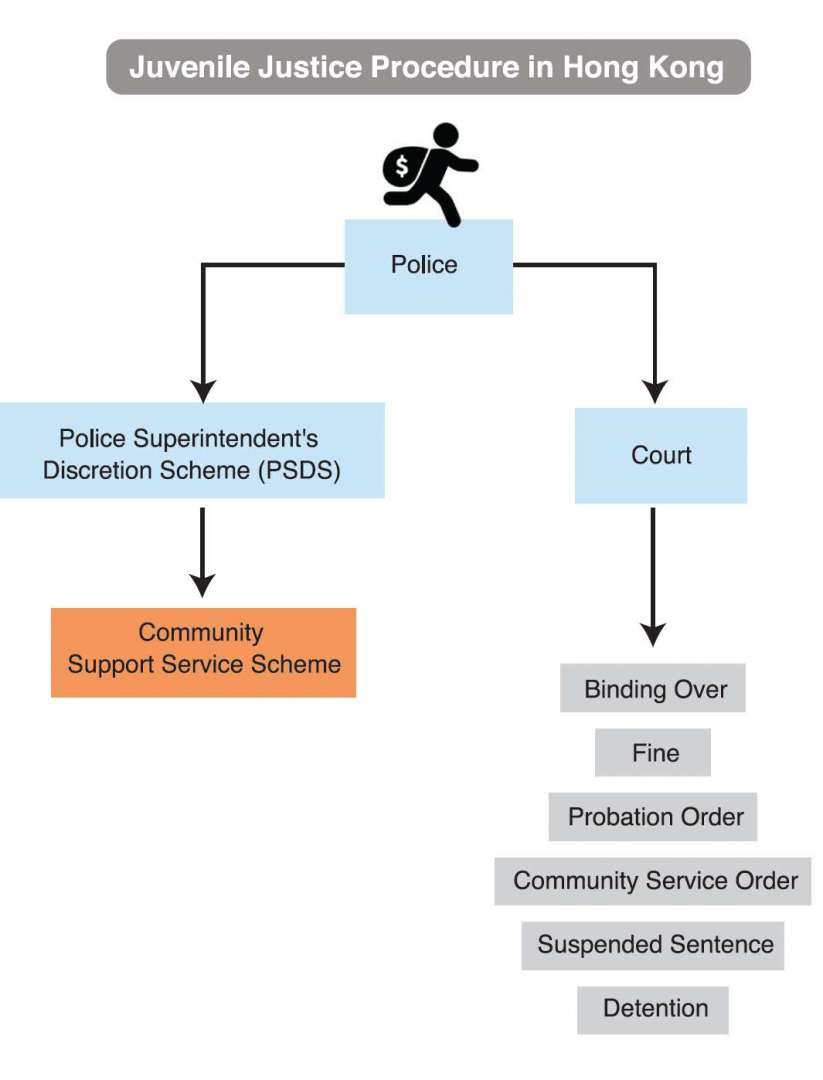

Hong Kong’s legal system has several approaches that echo this preventative approach, enabling young offenders to be held accountable for their criminal acts, while at the same time, not solely resorting to incarceration and punishment. Professor Wong argues that diverting these young offenders away from a formal criminal justice system can decrease the likelihood of future delinquency and recidivism.

While all may have room for improvement, Professor Wong remains a strong advocate for these approaches, as he discusses them individually with Youth Hong Kong.

Police Superintendent’s Discretion Scheme

The Police Superintendent’s Discretion Scheme (PSDS, 警司警誡計劃) applies to juveniles aged between ten and under 18 who have committed less serious offences for the first time. Under this Scheme, a young offender can be given a caution in lieu of initiating prosecution. Very often, the case can then be handed over to five non-governmental organisations that provide community reintegration support services. One of the NGOs tasked with this responsibility is the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups.

For those who reoffend or commit more serious crimes, offenders still have to face sentencing in court and may be put in custody under the Social Welfare Department (SWD) or the Correctional Services Department (CSD). When dealing with those offenders, the latter adopts a training model that is “Short, Sharp, Shock,” known for its rigorous discipline and tough physical training.

According to Professor Wong, the advantage of this measure is that some first-time juvenile offenders do not need to go to court once the police issued PSDS, because once they go to court, there will be a labelling effect, which may make these young people feel that they are irredeemable criminals. “If we only handle it at the police station level, do not prosecute them, and provide more encouragement and counselling, these juveniles may not commit crimes again,” he added.

While at some level, non-negative shaming practices may encourage some juveniles to turn away from re-committing offences, Professor Wong urges caution as well. “Some believe this method may not be effective because many young people come from broken families or difficult social environments. Their criminal behaviour may not always be a personal choice, but rather influenced by their surroundings, especially their peer group.” Therefore, if the PSDS is to succeed, it needs to take into account the original environment from where these young offenders come from.

Therefore, to fully understand these factors and mitigate the risks, Professor Wong believes there is still room to improve the mechanism, emphasising the need for a more widely employed assessment system to improve the success rate of rehabilitation.

Young Offender Assessment Panel

For more serious crimes, the Young Offender Assessment Panel (YOAP, 青少年罪犯評估專案小組), is adopted more widely in other judicial systems than it is in Hong Kong. For example, in England and Wales, panels similar to the YOAP have been set up since the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, engaging social workers, police, correctional service officers, nurses, psychologists and medical professionals who make a comprehensive assessment of young offenders.

Hong Kong’s YOAP was set up by both the CSD and the SWD to provide coordinated professional views to magistrates or judges in sentencing young offenders, who study and interview cases. They also suggest the most appropriate rehabilitation programmes, as well as offer advice to the Department of Justice.

In Professor Wong’s view, the Panel can be a key to providing future rehabilitation and helping young offenders reintegrate into society. However, he thinks it needs to be more widely implemented. “Hong Kong will need to widely adopt this assessment panel in the future for a more effective approach.” He also notes that the shortage of health professionals in the city is one of the main obstacles.

One recent criminal case where the judge assigned the YOAP in Hong Kong involved two young defendants in the vandalism of the grave of Wong Ka-Kui, the deceased lead singer of the band Beyond. The younger defendant was found to have a history of behavioural issues, including autism and hyperactivity, and was reportedly influenced by negative online communities. The older defendant had prior arrests for fraud-related offences. Considering those factors listed by YOAP, the judge decided that implementing a disciplinary detention sentence for both defendants would assist in their rehabilitation and reintegration into society, rather than simply punishing them.

Desistance Model

Apart from the YOAP, Professor Wong highlighted the Desistance Model, a comprehensive framework that emphasises the importance of social support, personal agency, and the development of a non-criminal identity. It is a process through which individuals cease engaging in criminal behaviour by changing their identity and self-perception, increasing stability, and strengthening social support.

This framework is being gradually implemented across Hong Kong’s government rehabilitation facilities, including Tuen Mun Children and Juvenile Home under the SWD and Phoenix House under the CSD, to provide more systematic and effective support to help young offenders reintegrate.

The application of the Desistance Model emphasises the interplay between individual choices and social influences in the process of desisting from crime. By focusing on the importance of family support, positive role models, and community engagement, the model provides a framework for understanding how young offenders can successfully transition to a law-abiding lifestyle.

Restorative Justice

For Professor Wong, implementing Restorative Justice (RJ, 復和司法) in the judicial system is something very much needed, acting as an inclusive, harm-repairing process that engages victims, offenders, as well as the community.

“Such restorative meetings can enable both parties to meet, allowing victims to express their feelings, while offenders can explain their actions, apologise and compensate the victims. In relation to young offenders, RJ helps them understand the harm and grief they have inflicted on the victims as fellow human beings, rather than viewing them as mere objects. It is not about teaching them; it is about facilitating a face-to-face encounter between the offenders and the victims,” he said.

“In western countries, this has become a common practice, but it has not been adopted in Hong Kong. There is still much room for improvement in Hong Kong,” Professor Wong said.

These Restorative Justice practices, according to him, have not been implemented very well in Hong Kong’s judicial system, society or amongst non-governmental organisations compared to Europe, but efforts have been made within the community by social workers and scholars, who, in 2000, established the Centre for Restoration of Human Relationships (CRHR, 復和綜合服務中心) to implement RJ in schools, dealing with serious conflicts between students.

Why focus on schools? Given the highly competitive nature of Hong Kong society, along with its dense population, Professor Wong argues that personal development must be part of the educational process. Juvenile gangs and bullying very often start in schools, and nipping this type of behaviour in the bud might have long-term repercussions on how people treat each other.

Taking school bullying for example, Professor Wong explains in the paper the vicious cycle of criminal behaviours, where a victim becomes a bully, and in turn, creates more victims and more bullies. “As teenagers enmesh themselves in bullying subcultures, they become insensitive to others’ feelings. So, instead of harsh disciplinary action, we favour the restorative practices of mediation and mending broken relationships in tackling bullying.”

Remaining Open Minded

Professor Wong fully understands that the different schemes offer different aspects of support that have their positive side, but they are not enough. He believes that the most crucial element is instilling the ability of young offenders to courageously take responsibility for their actions, acknowledge their wrongdoing, and make amends to society. Such a change in attitude could help them change their identity as criminals.

“We also need to teach them emotional intelligence skills, such as how to resolve conflicts, handle interpersonal relationships, be more tolerant and empathetic, control impulses, and learn problem-solving techniques, help them build skills and re-establish social bonding,” he said. The next step, he added, is helping them rebuild family relationships and re-establishing those important social connections with friends and the wider community.

Professor Wong believes that while the community generally accepts ex-offenders with less serious crimes, those who committed political offences or crimes of a more serious nature may face greater challenges when reintegrating into society. This calls for greater social acceptance if a safer and more inclusive environment is to be built. ■