//16.2 Perspectives: Running AI

Pushing Boundaries with AI

by Pili Hu

Pili Hu explains how AI helped turn him into an ultra-runner. But is that enough?

“What will be the last thing crushed by AI?” My response to this oft-asked question was running, specifically trail or ultra-trail running which covers hundreds of kilometres nonstop, through the mountains, day and night.

From Sedentary to Mobile

By the time I was 30, I was a workaholic leading a sedentary lifestyle. I was overweight and suffered from chronic shoulder and neck pains. With x-rays showing no fractures, I was then suspected to have contracted an uncommon skin disease, which doctors had little experience in treatment. All that they could offer me was a trial-and-error treatment, prescribing different antibiotics, one for every six weeks, to observe the results.

After three rounds of antibiotics, I figured that it was not helpful and began to consider whether my chronic pains might be because of my weak muscle groups and excess body fat. If this was the case, then all the signs for remedy pointed to a new direction: sports.

What happened next was life-changing. As I began hiking, running, and even learning how to swim, I saw how these endurance activities optimised my endocrine system. I lost 20 kilograms, and my health issues gradually disappeared.

These positive outcomes encouraged me to push further, especially with trail running. If the enjoyment of simple running was just a lucky by-product of being active, then becoming an ultra-runner had to be a well-engineered process.

From Mobile to Active

I first learned about ultra-running from the book Born to Run, which shared the stories of the Tarahumara people who are natural runners and the athletes who raced with them. I learnt practical techniques about running, while also being encouraged that anyone could be a runner. In one chapter, for example, the author explained 10 ways that human biological systems and physiological structures were precisely engineered towards distance running. The key was to run farther, not faster.

This was the “Eureka” moment of my ultra-journey. I had to re-think that what I had learnt as a child – to run fast – was no longer valid and I began to gather knowledge through research. I studied over 10 books, dozens of research papers, and even watched countless YouTube videos to come up with my own personalised training plans.

Getting Technological

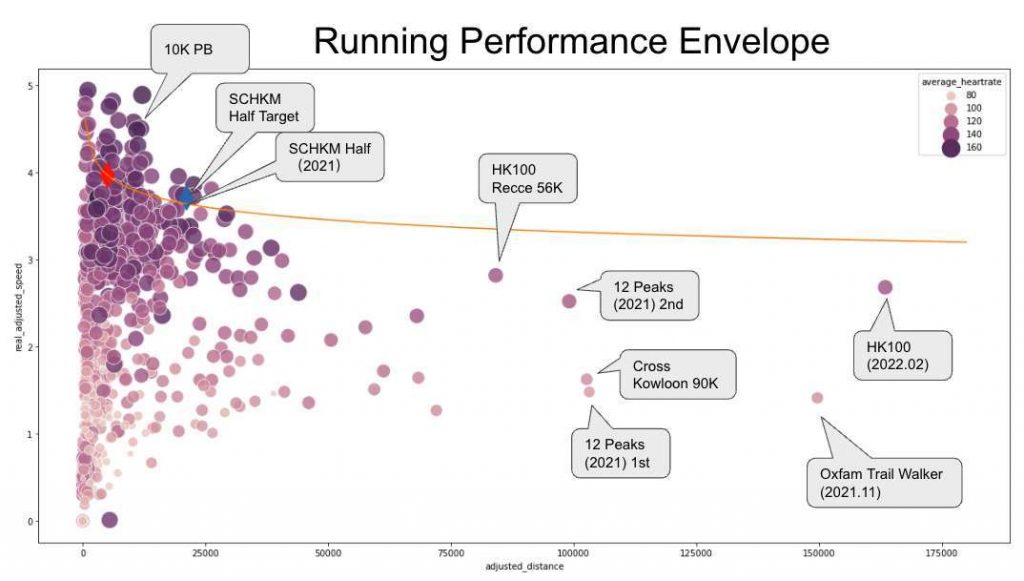

As a data journalist and data scientist, the first thing I needed to do was collect accurate data about myself. So, I got my first sports watch and came up with a visualisation plan. I learnt how to plot my running using other people’s formulae and became more conversant in my abilities. I was then able to plot and visualise my own trainings and develop what I call a Running Envelope. Simply put, this is just setting individualised goals for oneself to achieve the goal of running longer and safer.

One year after I started this type of structured training, I was able to accomplish several goals: completing the classical ultra running event Hong Kong 100 race in 17 hours. Two years later, I ran both the Hong Kong 100 and the Standard Chartered Hong Kong Marathon back-to-back, with a total distance of 234km in four days!

Pili Hu stands at the finish line of HK100, an ultra trail running event held annually in Hong Kong.

Running Coach of the Future

None of my achievements, I believe, would have been possible without the incorporation of data and technology, including Generative AI, to analyse my data and make predictions about how I needed to adapt, improve or adjust my running.

Technology is likely to play an increasingly significant role in sports training. One day, AI may appear in the form of smart glasses as real-time running assistants, who understand the course, your heart rate, weather, and lighting conditions. Once these tools become manifest, these AI assistants could provide guidelines, alerts, and advice on nutrition and hydration. The ultimate goal is for AI to manage the details, allowing humans to focus on running.

So, was I right that ultra-running would never be crushed by AI? My response is Yes and No.

Yes, in that AI can provide us with the logistical and mathematical formulations in terms of our own efficiency and even capacities as runners. No, because the advantage we have over machines is our efficient energy storage system which machines cannot compete with. With 1 kilogram of fat, humans can run 100 kilometres, whereas an electric vehicle needs a ton of batteries to store enough energy to move similar distances. As running coaches, they still lack the human touch to help motivate, encourage and cheer us on to cross the finish line, no matter how exhausted, injured or defeated we might feel.

A common question for ultra-endurance athletes when they are 90 kilometres into the race, with their energy exhausted and blisters on their feet, is: “Shall I quit?” A model may provide an accurate but verbose answer: “Based on your physical condition, you have a 60% probability to finish strong, 30% probability to finish with some injuries, and 10% probability to exhaust before the finish line.” While accurate, this may be the least useful answer to address this mental challenge.

The AI coaches may well understand how to train our bodies, but it is the human coach who can help push the real boundaries. ■

Pili Hu is a data scientist and the founder of the Institute of Endurance Science and Technology (IEST). With a vision that everyone can excel in sports and endurance exercise, IEST is an endurance running community that advocates scientific training, rationale racing and lifelong exercising. Go to iest.run to learn more.