//vol.16-1 Youth Watch

A Global Look on Mental Health & Ways to Heal

by Stella Chen

This article highlights statistics and practices, as well as how different countries and regions address mental health-related issues, from improving health literacy to adopting supplementary treatment approaches.

The pandemic has exacerbated existing mental health problems and triggered new ones, particularly among young people. In October 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) organised a roundtable meeting on online mental health content for young individuals, bringing together international experts to discuss the potential of social media and digital technology in expanding mental health promotion and reaching out to neglected youth.

As mental health is increasingly discussed, in schools, online platforms, and workplaces, it is crucial to assess progress made in enhancing awareness and improving access to support.

A worldwide perspective on mental health:

According to surveys conducted by Harvard Medical School and the University of Queensland in 29 countries, half of the global population will experience a mental health condition at some point in their lives. Female respondents showed higher rates of anxiety and mood disorders, while alcohol use disorder and major depressive disorder were more prevalent among male respondents.

According to data from the World Health Organization, one in seven individuals aged 10-19 worldwide lives with a mental disorder, accounting for 13% of the global disease burden in this age group. Key factors contributing to mental health issues among adolescents include depression, anxiety, and behavioural disorders like Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

Institutional or community-based psychiatric care?

As mental health policies have evolved in countries with diverse financial and social backgrounds, discussions have arisen regarding deinstitutionalisation. This movement advocates for a shift from primarily hospital-based psychiatric care to mental health services provided in less isolated community settings. Instead of relying on medication and long-term hospitalisation, more countries are exploring alternative, individualised, and time-unlimited community-based services. These reforms encompass aspects including holistic wellness, housing, and interpersonal relationships, while fostering collaboration between healthcare and social welfare sectors.

Australia

Australia launched the Act-Belong-Commit Campaign, a community-based initiative in 2005 to encourage people to be proactive about their mental health and well-being. Using a social-franchising model, the Campaign seeks partnerships with different categories of organisations, including government agencies, health services, local community groups, and schools to provide mentally healthy activities. “Do Something!”, “Do Something with Someone!” and “Do Something Meaningful!” are the key phrases of the Campaign, showing its aim to help people keep active, and find connection and self-worth in their lives, hence improving mental well-being.

The United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, mental health charities Mind and Rethink Mental Illness established Time to Change in 2007. The programme uses local community projects, national high-profile campaigns such as national advertising and social media, mass-participation physical activity week and training for student doctors and teachers to change society’s behaviour towards people with mental health problems and end discrimination faced by this group.

New Zealand

The Ministry of Health in New Zealand launched Like Minds, Like Mine, the first nationwide anti-stigma on mental health campaign in 1997. The programme uses community activities, education workshops and mass media advertising campaigns to break down stereotypes faced by people with mental illnesses. The Famous People Campaign, for example, was launched in New Zealand to raise awareness and tell stories about how famous people were affected by mental illnesses.

Turkey

Turkey continued the tradition of large mental health institutions focused on in-patient care, which originated in the late Ottoman era. In 2006, the country introduced a comprehensive programme to provide accessible community-based mental health services by establishing 177 community mental health centres. To address the lack of specialised community services for younger populations, a specialised Department for Children with Autism, Mental Special Needs, and Rare Disorders was established in 2020.

Africa

With mental health conditions largely untreated in many parts of Africa, grassroots community-led initiatives are bridging the gap by educating and training lay health workers to deliver personalised treatment and support. Most African governments allocate less than 1% of their healthcare budget to mental illness. Seeking psychiatric help is often stigmatised in African cultures, with the belief that individuals with mental health disorders may be possessed by evil spirits. To bridge the manpower gap in community mental health care, Uganda and Zambia have established community-led programs like Peer Nation and Strong Minds to train lay workers with lived experience of mental health challenges, link people who have mental illnesses to specialists and provide peer support.

Indigenous Healing Methods

Indigenous culture

Indigenous communities, with their rich traditions and longstanding connection to their native lands, often favour complementary or alternative approaches to mental health as opposed to conventional services. For instance, American Indians and Alaska Natives rely on traditional healing methods, through seeking guidance from spiritual healers and community elders, who use traditional medicine and herbs like infused oils, sage, and sweetgrass in ceremonial practices to alleviate emotional distress.

While Western psychology focuses on treating the individual and promoting autonomy as a measure of health and well-being, indigenous cultures view the world as an interdependent system where the universe, natural environment, and community are all connected to holistic wellness. They put less emphasis on therapy sessions but rely on sacred and traditional ceremonial practices that align with the holistic environment.

India

Ayurveda, a Sanskrit word meaning “science or knowledge of life,” originated in India over 5,000 years ago and is one of the world’s oldest holistic healing therapies. Rooted in the philosophy that health and wellness depend on a delicate balance between the body, mind, spirit, and environment, Ayurveda employs herbal treatments, dietary adjustments, and lifestyle practices to promote good health and prevent diseases rather than merely combating them.

Based on the belief that everything in the universe, living or nonliving, is interconnected, Ayurveda posits that disease arises from an imbalance or stress in a person’s consciousness. Ayurveda advocates self-care practices like oil pulling, massage, seasonal eating, incorporating spices into cooking, using herbal remedies to restore harmony among the mind, body, spirit. These practices help individuals cultivate introspection, mindfulness, and a deeper understanding of their true selves for mental nourishment.

Japan

Reiki, a Japanese technique for healing energy, aims to enhance well-being by tapping into universal life forces and is believed to be beneficial for reducing stress, inducing relaxation, and enhancing overall well-being. The term 「Reiki」 originates from the Japanese words 「rei,」 meaning universal, and 「ki,」 signifying life force energy. Mikao Usui, a Japanese Buddhist monk, established this practice in the early 1900s after claiming to have gained knowledge about Reiki through a spiritual encounter on Mount Kurama in Japan.

Based on the belief in a universal life force energy that flows through all living beings, Reiki practitioners use their hands to direct this energy and promote healing and balance in the body, mind, and spirit. By placing hands on or hovering them over the body, they transmit this energy to the recipient. Reiki has gained popularity as a complementary therapy worldwide, including in the United States.

Mexico

In Mexico, where access to mental healthcare remains limited and psychotherapy is sometimes stigmatised as a service only for severe mental illness, alternative therapies have emerged to address emotional needs.

Family constellations, a therapeutic yet some claim to be pseudoscientific methods originating from Europe and Africa, focus on the significance of family bonds and were introduced in the country to help individuals ease trauma passed down through generations of families affected by long-term conflict and violence. Unlike traditional psychotherapy, which primarily focuses on the client’s narrative, family constellations connect a person’s network of relationships to understand how family conflicts, oppression, and emotional bonds influence their mental well-being.

Norway

Norway has introduced a drug-free treatment approach for individuals with psychosis who wish to recover without medication. This alternative method aims to address the severe side effects associated with antipsychotic drugs.

The drug-free treatment programme in Norway was established in 2016 and is available through the national health system. It provides patients with an option to receive medication-free care, focusing on alternative therapies such as art therapy. Although the drug-free treatment programme has received support and positive outcomes, it remains controversial in Norway. Critics argue that it is driven by ideology rather than evidence. ■

References:

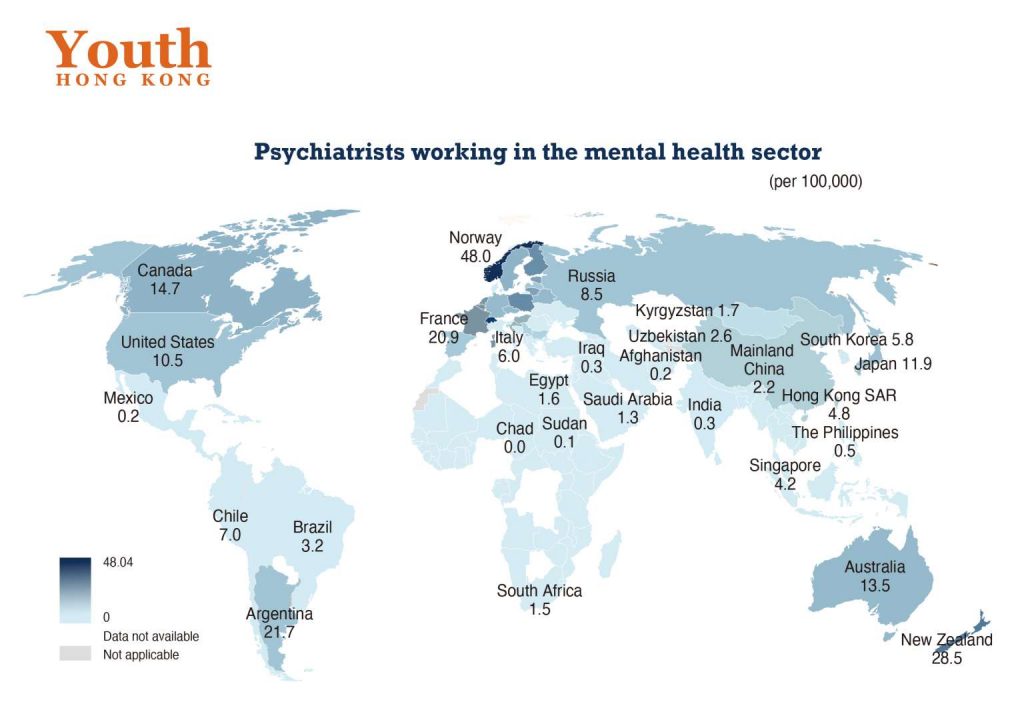

- Psychiatrists working in mental health sector (per 100,000), World Health Organization

- Mental health of adolescents, World Health Organization

- Report of a virtual roundtable meeting on online mental health content for young people and guidance on communication, 4 October 2023, World Health Organization

- Age of onset and cumulative risk of mental disorders: a cross-national analysis of population surveys from 29 countries

- Treatment and follow-up care for psychiatric patients, the Government of HKSAR press release

- Mental Health Review Report, 2017, the HKSAR Government, Food and Health Bureau

- How Africa heals as community-led mental health care makes inroads

- How Do Other Countries Deal With Mental Health?

- When pipe ritual helps more than talk therapy, the Harvard Gazette

- Native American communities prioritize traditional healing to treat mental health

- An Alternative Therapy Hits Home in Mexico

- How reiki can help with your anxiety, grief, stress, chronic illness and more, the SCMP

- How Ayurveda Helps In Improving Mental Health

- How Norway is offering drug-free treatment to people with psychosis

- The Act-Belong-Commit Guide to Keeping Mentally Healthy

- Promoting mental well-being in Western Australia: Act Belong Commit® mental health promotion campaign partners’ perspectives

- Time to Change