//vol.16-1 Interview: Professor Paul Yip

Turning Off the Tap

An interview with Professor Paul Yip

Professor Paul Yip Siu-fai, Chair Professor on Population Health and Director of the Hong Kong Jockey Club Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention (CSRP) of The University of Hong Kong, shared his thoughts on the mental health problems in the city and the complex factors contributing to this challenge, particularly among young people.

The key to tackling this issue, he said, lies in how to change our mindset, from simply “floor mopping” to addressing the source of the “water leak.”

Emerging Challenges

According to Professor Yip, the increasing global awareness of mental health issues has fostered a more open space for discussion. However, he also highlighted a gap in how professionals are addressing the issue, potentially due to a generational gap in understanding, coupled with what he termed as 「intellectual laziness」 and confusion of concepts.

“Today’s youth face more complex challenges than in the past. Older generations find it hard to understand what young people are going through because the environment they’ve grown up in is vastly different. We can no longer apply our past experiences trying to understand them,” said Professor Yip, underlining the widening generation gap and the erosion of trust between parents and children nowadays.

The further impact of rapid social changes, the prevalence of social media, and shifts in family and population demographics, such as low birth rates, an ageing population, and an increase in single-parent households or one-child families, introduces new challenges to the mental health of young people. These challenges are further exacerbated by long-standing stressors, including a highly stressful and performance-rewarded educational system, close living quarters, limited public space, and rising parental expectations.

Leaking Taps

So, what is the answer? Is it possible to make Hong Kong a happier place? “There is no silver bullet or magic pill,” said Professor Yip, calling for a more comprehensive approach and multilayer intervention. “We also need a critical examination of the countless measures and initiatives already in place, and examine their effectiveness, and relevancy to determine whether we are on the right track.”

“What we see,” pointed out Professor Yip, “is that authorities, for a long time, have focused on those who have already been diagnosed with mental health issues, with few resources allocated on the prevention of symptoms from becoming clinical.”

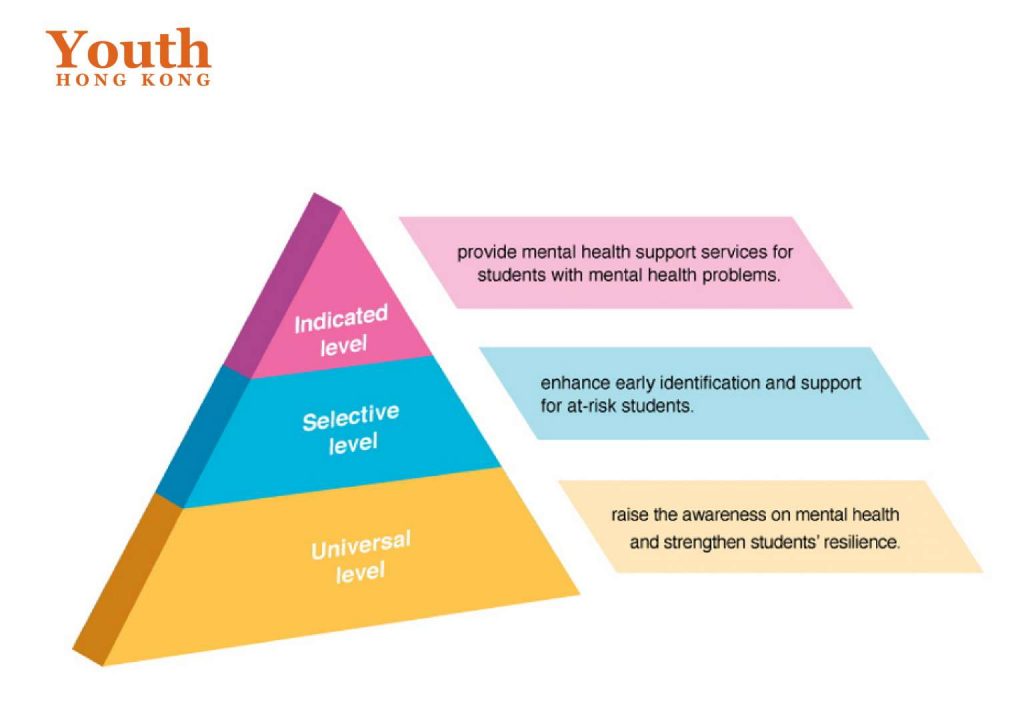

This might be a result of the common misunderstandings towards the frequently discussed three-tier support model, which includes the three levels of approach, namely indicated, selective and universal to support those with different mental health needs.

Through this example, officials and intellectuals tend to focus on those in the first indicated tier, providing health support services for those who are already under care, and missing out on early identification and building resilience among seemingly healthier individuals. As Professor Yip states, “Prevention is always much more effective than cure, especially because our service capacity is on the edge already.”

He explained further, “I often use a simple analogy. Our kitchen is flooding and everyone is busy mopping the floor. The government, NGOs, parents and schools are all putting in tremendous effort into this ‘clean up,’ but no one is addressing the root cause. What is making the kitchen flood? We need to identify leaks in the sewage system or turn off the tap. Yes, it’s necessary to mop the floor for immediate effect. However, it’s more important to look into the actual problem we are facing. We need to look at the downstream and upstream problems simultaneously.”

Finding Solutions

In locating the leaking tap, there is a need to acknowledge and deal with the very real problem, and not just in Hong Kong, of a shortage of medical resources, while also ensuring a more mature assessment system is in place, perhaps by applying the stratified stepped care approach to access the severity and providing the most suitable care services.

Beyond medical interventions, what Professor Yip suggests is building up a “more supportive and empathetic environment” as one of the most effective approaches. In that case, more individuals can be equipped with basic skills such as mental health first aid. So if professional help is not readily accessible, a safety net of peers, teachers, social workers and family members are there for those who are struggling for conversation and support.

“The solution lies in revisiting support systems for students and strengthening the ties between students, teachers, and families. For those in education, this can include improved communication, reducing homework and providing students with space and real holidays to build a more supportive educational environment,” said Professor Yip, emphasising that going to school should be an enjoyable experience. “My concern is that the education system unintentionally creates a culture of failure with all the celebrations on success, which I believe requires attention and reflection on this critical issue.”

However, in a fast-paced society like Hong Kong, establishing such connections is challenging, and parents and teachers may not have the time and energy to provide the needed emotional support. How is it possible to pay attention to the younger generation when teachers and parents themselves are grappling with mental illnesses? There’s a deeply rooted cultural influence that must not be overlooked.

This is why, Professor Yip argues, “Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) should not only be focused on the volunteer hours of employees and the donation made to the others. It should also demonstrate ethical and socially responsible ways to make money, and to treat employees better, even in universities and schools.”

A Small Caring Community

With regard to young people, “I think first of all we need to learn how to value them better. We need to understand their needs and concerns, let their voices be heard, appreciate their diversity, and not apply a one-size-fit-all mentality,” he added.

Professor Yip concluded that each one of us can work on building a more caring small community, where we all make collective efforts. “Don’t underestimate the power of each individual. By supporting our children, spouses, family members, and friends around us, the world will be different. If everyone does the same, we will create a more caring environment for not only young people but for all of us that can lead to the building of a healthier city.” ■

References:

- More people showing symptoms of depression: survey

- Dynamic reciprocal relationships between traditional media reports, social media postings, and youth suicide in Taiwan between 2012 and 2021

- Epidemiological changes, demographic drivers, and global years of life lost from suicide over the period 1990–2019