//vol.15-4 Interview: Dr Siu

A Tale of More Than Two Cultures

When we place an order for an afternoon tea set featuring French toast at a neighbourhood Cha Chaan Teng, it is easy to overlook the cultural and historical factors and how they got there.

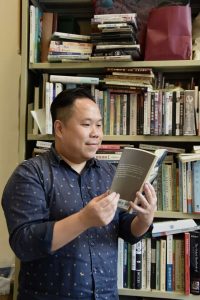

Youth Hong Kong had a conversation with Dr Siu Yan-ho, a lecturer at Hong Kong Baptist University’s department of Chinese Language and Literature, about the significance of food in history and literature studies, as well as Hong Kong’s changing food identity.

The year 2003 marked a turning point for Dr Siu. In a French restaurant on Leighton Road in Hong Kong’s Causeway Bay, Siu’s career working as a chef had just begun. That very year, however, the outbreak of SARS disrupted the city, grinding its catering businesses to a sudden halt.

The 19-year-old, facing a professional setback, decided to go back to school at this crossroads of his life. “Fortunately, or unfortunately, whichever way you choose to look at it, my life took a completely different turn. I tried my best in studies, realising that a career in academia might offer more stability,” Siu reflected.

But his connection with food did not come to an end. Dr Siu is now piecing together the puzzle of Hong Kong’s unique food culture.

Through the Lens of Food

Food, in the academic world, is more than a basic human need, but another dimension to interpret social and cultural histories. For Siu, studying history and literature through the lens of food helped him gain a deeper understanding of these disciplines, as well as interpreting movies, poetry and novels.

In studies on Hong Kong’s modern literature, writer Liu Yi-chang, an immigrant from Shanghai who lived in North Point, often referred to as Hong Kong’s 「Little Shanghai,」 portrayed the migration of Shanghainese culture to the city, including the introduction of the Russian soup, Borscht, from Shanghai in the 1960s. While studying immigrant history and the social context of Hong Kong, Siu examined this culinary shift and its implications for the characters depicted in Liu’s novels.

“From the perspective of food, we can take a close look at the relationship between individuals and the historical space they once inhabited. There’s always more to explore: people, family dynamics, education background, and social strata,” said Siu.

Hong Kong Food

Where does our food come from? It is a multifaceted subject that is related to many factors. Unlike French, Cantonese or any other types of cuisine, according to Siu, there has been a gap in the official records documenting the culinary history of Hong Kong which is worth studying about.

Under the initial influence of Cantonese cuisine, Hong Kong food is known for its unique blend of Eastern and Western influences since it became a British colonial outpost in 1841. The international trade hub later saw the influx of immigrants from mainland China and other Southeast Asian countries, introducing more diverse identities to its food scene.

This has resulted in the history of Hong Kong cuisine, particularly its Cha Chaan Teng culture, has become a subject of interest for scholars. Where a typical Hong Kong Cha Chaan Teng menu boasts an array of iconic dishes: macaroni with sliced ham, French toast, pineapple buns, baked pork chop rice, and milk tea, the history behind those dishes is often left unnoticed.

What you should know

Cha Chaan Teng:

A type of Hong Kong-style restaurant that serves affordable comfort food, including Hong Kong-style milk tea. The name literally means 「tea restaurant」 in Cantonese

Yum Cha:

A Hong Kong tea tradition that involves drinking tea and eating Dim Sum, which are small dishes typically served in bamboo baskets.

Dai Pai Dong:

Licensed food stalls that originated in Hong Kong after World War II. They serve affordable food, but the environment is not visually attractive. The food is quite different from that served in Cha Chaan Teng.

For example, the afternoon tea period which we see in almost every Hong Kong restaurant is unique when compared to Macau and Taiwan. Siu believed that this dining time period bears traces of British influence, although the food is not the same anymore.

The blend or fusion, in Hong Kong cuisine, results in an inability to place Hong Kong food in any genre, with not a single element to be claimed as originally native to Hong Kong.

“When Hong Kong people are asked to cook Hong Kong style cuisine on a cultural exchange programme, some would make egg tart or French toast. Then French people will question: are you copying our food? You can definitely say that, but Hong Kong food is still different.”

Cultural Identity Crisis

As Hong Kong’s food scene continues to evolve with its unique and diverse flavours, it also unveils a cultural food identity crisis, especially among young people.

“The past generation were brought up by parents taking kids to eat Dai Pai Dong, Dim Sum, Cha Chaan Teng, where big family gatherings were the norm. Families used to play such an important role in passing down food culture, but it is becoming increasingly difficult nowadays,” Siu said.

Different from the 1980s and 1990s, more dining options ranging from Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Thai, Indian and Taiwanese are now ubiquitous in Hong Kong. This expansion, unfortunately, has been accompanied by a significant decline in traditional Cantonese and Hong Kong-style eateries even before the Covid pandemic. The dilution of local cuisine tradition leaves us pondering how to preserve Hong Kong’s distinctive food identity.

“The industry is highly commercialised, where you see the whole streets lined up with trendy establishments specialising in chicken pot, Sichuan grilled fish, and rice noodles. While we have gained an abundance of dining options, there’s also been a gradual shift of our culinary identity,” Siu said.

Highlighting the need for a more sustainable and resilient approach, Siu pointed out that the Covid pandemic has brought numerous underlying issues in the food and beverage industry to the forefront. Due to declining revenues, a bunch of local restaurants are forced to close, leading to experienced chefs leaving the industry. Meanwhile, market demand, particularly for mid-tier restaurants, remains low due to economic pressures, fewer options and lower food quality.

Will traditional Yum Cha sessions or Cha Chaan Teng shut down and go unattended in the future? To address these issues and safeguard the city’s culinary heritage, Siu proposed a long-term solution by documenting traditional food culture and inventing new culinary trends for future generations. This approach would make culinary heritage vibrant and relevant in a globalised and ever-changing landscape of global cuisines. ■