Hong Kong’s bilingual comedian Vivek Mahbubani reveals his funny formula and why being the “odd one out” made his story.

When we step into a bookstore in search of a new novel or gaze at cinema posters picking up films to watch, we are on a quest for a story that captivates and resonates with us. Each narrative, whether joyful or sombre, thrilling or melancholic, unfolds with its highs and lows, with the flaws of each character.

Stories allow us to connect, and language serves as the vehicle for our emotions. It’s those imperfect elements and vulnerability that push the narrative forward, make the work unique, relatable and authentic. This philosophy is at the heart of Hong Kong stand-up comedian Vivek Mahbubani’s comedic approach.

“No one wants to watch a movie featuring characters with flawless lives. I’m not flawless either, so when I perform, I use my quirks and imperfections to tell stories that others relate to,” says Vivek.

Born and raised in Hong Kong, Vivek grew up in an Indian household, but at school, everyone spoke Cantonese. As the only one from an ethnic minority background, he never seemed to fit in, no matter how hard he tried. He was always the odd one out.

Vivek uses both English and Cantonese to express himself, showing audiences how he copes with life’s challenges to reveal his sense of identity. He says stories allow us to connect with others, and using two languages as a vehicle for emotions lets him make people laugh about how he tries to make sense of the world.

Comedy = Tragedy + Time

Growing up watching TV, the comedians he saw always amazed him: how they mastered language with such a simple tool as a mic.

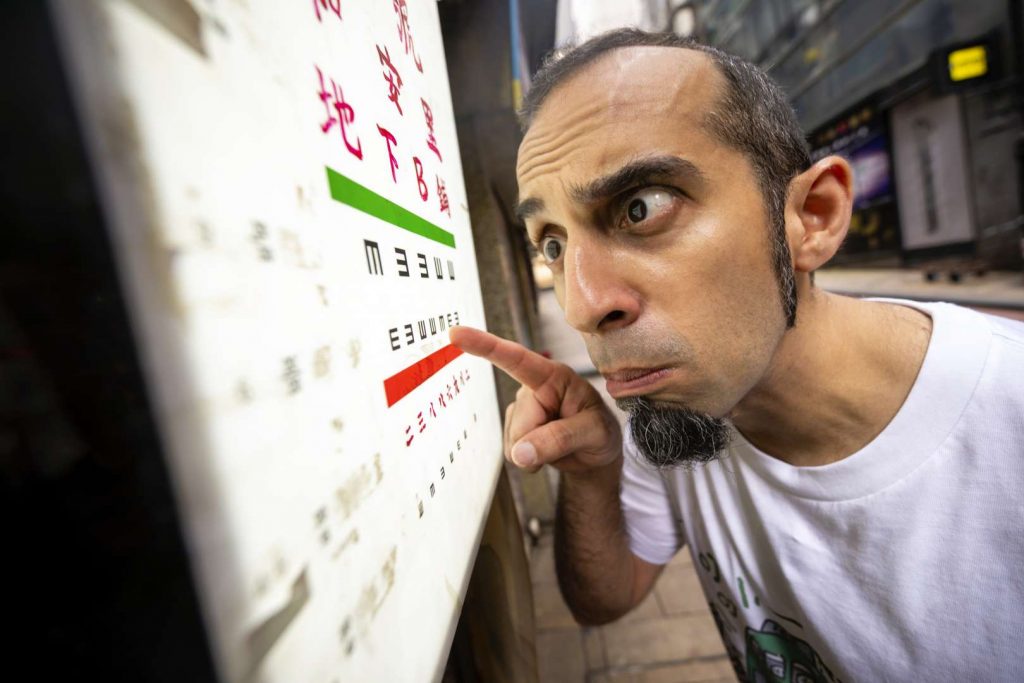

“I was very confused,” says Vivek, with his quizzical signature look. “What is it about this person on TV talking into a mic that’s so funny? At school, my teacher used a mic too but it wasn’t funny?”

Vivek was intrigued and promised himself he would try stand-up comedy too. He had no deadline — until a health check-up in 2005 gave him one.

In 2006, Vivek was diagnosed with lymphoma. Like everyone else, he reacted to the word “cancer” with a sense of gravity. “I thought it meant the end of life. In the movies, cancer usually means losing your hair and dying — so sad, right? But the doctor told me I had a second chance with daily chemotherapy.”

During six months of chemotherapy, he realised he needed to grab what might be limited time to get things done, whether seeing a friend, reading books or achieving his dream of being a comedian. When he finally started to get better in 2007, he saw an advertisement for a stand-up comedy competition. “I thought: this is it. I promised myself I would try comedy before I died. Who cares? If I can survive cancer, what’s the worst that could happen if people don’t laugh?”

Vivek seized the opportunity and won the championship in the Cantonese category, followed by a victory in the English category the next year. Since then, he has been a humorous presence in Hong Kong’s comedy clubs, international comedy festivals and corporate events, with numerous awards earned locally and abroad.

Vivek’s career as a comedian draws inspiration from life’s bitter experiences but also from the seemingly trivial everyday moments: looking at passengers on the MTR, watching people in lifts, buying pens at a stationer’s. He jokes about encounters with misunderstandings, how he looks compared to local Chinese people, and his receding hairline. By turning what might have been weakness or unpleasantness into good 10-second laughs, he has found his way to let go of frustrations, deal with life and move on.

“There’s a formula called ‘comedy equals tragedy plus time’, so usually the funniest stories are not the happiest,” Vivek says. He considers comedy as both a sword to attack and a shield to protect. “With comedy, I can make fun of people by punching upwards and poking at those above me. That’s the sword at work. At the same time, when it’s about your own life and you joke about it, that works as a shield.”

Through his comedy, he seeks to make sense of a world where reality can clash with expectations. “I want to live in a world where everyone is my friend—yay! But in reality, that’s not the case.” He goes on to recall the experience of somebody barging into him on the street and telling him to “go back to Pakistan.”

In a situation like this, where an ordinary person would get furious, Vivek, an Indian, makes it into a joke. “I don’t see myself as a victim. Instead, I think, oh, he’s just telling me to go on a nice trip somewhere—he’s just got the wrong place!”

Comedy Across Languages

Vivek’s ability to speak two languages also gives him a unique perspective. By comparing expressions across Chinese and English cultures, he has learned about the cultural nuances and different ways of making jokes. This allows him to craft and deliver his stories in various “voices” to engage diverse audiences.

“Each culture has a different sense of humour, and the language of each culture is usually at the heart of understanding that humour. For example, in Cantonese, a highly contextualised culture, when someone responds to your idea by saying ‘咁都俾你諗到’, which means ‘wow, you thought of that?’ you need to pause and consider the social cues and context to determine whether they are being sarcastic or are genuinely complimenting you.” In contrast, a response like this in English could be perceived as different in the use of tones, Vivek explains.

Whenever he crafts jokes in his two languages, Vivek relishes the challenge of thinking in completely different ways, uncovering the nuances of each context, and achieving the same comedic effect with diverse audiences.

Would his life be entirely different if he had not attended a local school or spoken Cantonese? His answer is yes. “My life would have been much more regular if I’d only spoken English. But with two languages, I can enjoy jumping around. For that, I’m very grateful, even though it was sometimes a painful learning journey. It’s been very much worth it.”

Over nearly two decades of creating content, Vivek has found that the most exciting aspect of being a comedian has always been trying to find the funny side of life and transforming “rubbish into value.” Unlike bankers who must commute to their offices in Central to close deals, or teachers who are bound by fixed schedules in classrooms, Vivek can create jokes anytime, anywhere to make people laugh, in English or Cantonese.

Like Being a Jazz Musician

Stand-up comedy, a western import, is a relatively recent art form in Hong Kong, emerging in the late 1980s and gaining significant popularity in the 2000s thanks to pioneering comedians like Dayo Wong (黃子華). This niche cultural phenomenon has been localised and industrialised in various ways, including through streaming platforms and bar gigs. However, it faces challenges. Consumption patterns have changed, attention spans have fragmented, and social media dominates.

“People still want comedy and come to shows. It is not like waking up in a world where people don’t laugh anymore,” Vivek says, “But consumer habits are different. Before, people went to certain performers’ shows because they had seen them on TV. Now, it’s easier for stand-up comedians to get an audience if their Instagram is doing well and their reels are funny.”

While social media encourages a diversity of comedic content, it also makes it challenging for comedians to retain audiences. People are overwhelmed by online choices, whether it’s catching up on a show on Netflix or scrolling through endless short videos on social media.

“With so many options, people end up not watching anything or watching a bit of everything. It’s difficult to pull them away from their screens and encourage them to come to my 10-minute shows when they’re used to one-minute funny reels on phones,” Vivek admits. “It’s like comparing pop music to jazz. Do I want to perform for 60,000 people in a stadium or for 600 people in a bar? I’m like a jazz musician, I’ll take the smaller crowd — that’s the challenge.”

Now a 42-year-old storyteller, Vivek wants his power to draw in young people who feel lost and left out of the mainstream, to share their struggles and hardships and to help them with comedy and language quirks. He wants to let them know that everyone’s story is worth telling and that being different is not necessarily a bad thing.

“When I was young, I hated my life. I hated my identity; I’m an Indian, and it was always a headache to explain. Now I like being the odd one out. It’s about how you want to see it.” Reflecting on his own pathway, Vivek says don’t deny your story as the odd one out. “Not fitting in is itself a story, just as fitting in is. Once you have discovered your own story and you know it’s great, you find your own way to express it.” ■